Small Business Needed Federal Help. The Agency in Charge Fell Short.

The Small Business Administration, overwhelmed by demand from ailing entrepreneurs, has been slow to distribute aid needed to survive the pandemic

By Amara Omeokwe and Ruth Simon

June 17, 2021 12:06 pm ET

In the pandemic shutdown last year, three-quarters of the nation’s small employers turned to the Small Business Administration for help. The portfolio that includes loans issued or guaranteed by the federal agency swelled more than five times to nearly $900 billion.

The extraordinary demand has overwhelmed the SBA, best known for guaranteeing loans to small businesses, and left many entrepreneurs in limbo as they seek to recover. Business owners complain of unprocessed aid applications, waiting hours on the phone with questions that go unanswered and technological glitches. Its inspector general warned of signs of rampant fraud.

At the heart of many of the problems is the Office of Disaster Assistance, a little-known unit that issued nearly a quarter of the agency’s pandemic loan volume. In normal times, the office provides loans after floods and other natural disasters.

Since March 2020, the office has issued roughly $211 billion in pandemic-related Economic Injury Disaster Loans, three times as much aid as in the previous 68 years combined. In total, the office has provided roughly 9.8 million loans and grants totaling more than $230 billion, SBA data show. These pandemic responsibilities would have challenged even the best-run government agency. The office’s difficulties were compounded by the types of management and technological weaknesses identified over the years by government watchdog agencies.

“On the disaster side, we did a terrible job,” said Robert Scott, a former SBA Regional Administrator who spent several weeks in Washington early in the pandemic helping coordinate the agency’s response. “The existing systems in place, the existing leadership in place, just have not adjusted to what is necessary to meet the demand right now.”

Small firms accounted for 47% of the private sector workforce in 2017, the most recent data available, and after being disproportionately hit by the pandemic, they are lagging behind bigger companies as the economy reopens. Nearly one-third of small employers say it will take them more than six months to recover from the pandemic, according to a Census Bureau survey.

Business owner Samantha Harvey said glitches in an online application site in April made it impossible to submit documentation to request an increase in the amount of the disaster loan for her health-and-wellness company in Los Angeles. She said she called customer service three times and sent several emails but couldn’t learn what was causing the problem.

Roughly two weeks later, Ms. Harvey was able to submit the forms. She is still awaiting a decision.

Another request for a loan increase to support Ms. Harvey’s second business, a science communications and consulting firm, was denied because of a clerical error on her 2019 tax return, she said. Ms. Harvey tried explaining to customer service representatives that she had filed an amended return correcting the error. After trading several emails, she was finally told she had to begin a new, separate process to appeal the denial.

Dealing with the SBA “puts you in a state of confusion and doesn’t allow you to focus on what you should be doing, and that is to continue to rebuild your business after a pandemic,” Ms. Harvey said.

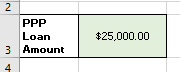

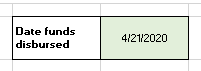

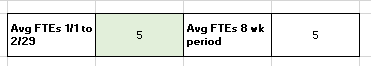

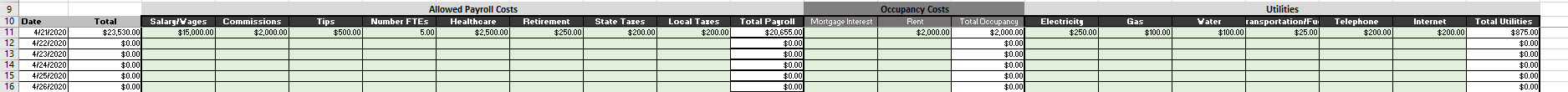

The SBA was responsible for administering the Paycheck Protection Program, which used private lenders to originate forgivable federal loans to pandemic-hit small businesses. The program, while hitting bumps, received bipartisan praise for issuing $800 billion in loans.

One problem was that the Trump administration gave priority to the PPP, to the detriment of the disaster office, said Sen. Ben Cardin (D., Md.), chairman of the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship. The disaster loan programs, he said, “suffered in the implementation speed, as well as the amount of resources small businesses should have been entitled to that they did not receive.”

SBA’s direct pandemic programs, including its new grant initiatives, are particularly important for minority-owned firms and businesses that may lack access to traditional financial institutions, he said.

The pandemic highlighted existing shortcomings in an office accustomed to dealing with natural disasters, usually in limited geographic areas. The Government Accountability Office had criticized the agency’s performance after Hurricane Sandy in 2012. It said the agency had made improvements by 2017 during Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria, but still flagged problems with customer service.

The GAO in March added the SBA to its list of high-risk government programs, citing evidence of fraud, program integrity risks and a need for greater oversight. KPMG, SBA’s independent auditor, declined to express an opinion on the agency’s fiscal 2020 financial statements, noting that the SBA had “inadequate processes and controls.”

Isabel Guzman, the SBA administrator since March, said the agency’s staff, including those in the disaster office, faced the challenge of rolling out national programs to help millions of small-business owners.

“We’ve worked really hard to shift our focus and be as customer-centric as possible, and that’s a work in progress,” Ms. Guzman said. She cited the SBA’s partnership with financial technology companies to accept applications for a new $29 billion restaurant grant program. It launched smoothly May 3, coinciding with the easing of pandemic restrictions on public dining.

In less than two weeks, the restaurant program, run by the SBA unit that administered the Paycheck Protection Program, had distributed $2.7 billion in grants.

Live entertainment, including music and theater, has also begun to return. Yet a new $16 billion grant program for live venues, run by the disaster office, hasn’t kept pace. Roughly six months after Congress authorized the program, the SBA has awarded about $304 million in grants. On Wednesday, more than 200 members of Congress signed a letter asking the SBA to explain the delays and speed the flow of funds.

Ms. Guzman said the program’s rollout was delayed because of how it was designed by law.

The agency in the past week revamped its process to speed up reviews of venue grant applications, an SBA official said. Before the change, the process made it easy to shift responsibility for approvals from one person to another, delaying decisions, the official said. The SBA unit overseeing restaurant grants also recently began advising the venue program.

Call waiting

Customer service problems at the SBA, long an issue, have been particularly acute in the past year. Some callers last year waited more than four hours to reach a customer service representative, the inspector general said in an October report. The SBA said average wait time has dropped to less than 90 seconds.

The SBA’s customer service agents can answer basic questions about Covid-19 disaster aid, but early in the pandemic most representatives didn’t have access to applicant files. They can now provide status updates and insert notes into files, the SBA said. Yet many business owners continue to report that service agents can’t answer their questions about how to resolve issues that may be delaying their aid approvals.

Callers are sometimes referred to SBA’s 68 district offices, where local businesses usually go for help. District office workers can check the status of traditional SBA-backed loan applications, but for much of the pandemic they didn’t have access to applications submitted to the Office of Disaster Assistance.

“Every week, we would say, ‘Why can’t people in the field have access to the ODA system?’ ” said Michael Vallante, a former SBA associate administrator in charge of field operations who left the agency this year.

Ms. Guzman granted field offices access to loan files within days of taking office in March, the agency said. The SBA attributed the previous policy to the Trump administration.

The disaster office, which operates largely independently from the rest of the agency, has been led since 2009 by James Rivera, a career civil servant. He became a disaster loan specialist in 1989 and was put in charge of revamping the unit after criticism in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Mr. Vallante, Mr. Scott and other former SBA officials said Mr. Rivera and his leadership team were reluctant to share information or take suggestions. The SBA didn’t make Mr. Rivera available for comment but said he was committed “to strong and close coordination” with field offices and others.

Congress charged the disaster assistance office at the start of the pandemic with issuing grants to small businesses, something it had never done. The SBA distributed $20 billion in grants last year, but it has been slow to hand out the $35 billion in additional grants authorized by Congress more recently. As of June, the SBA had approved nearly $1.8 billion of that money.

ABC Airbrush in Dalton, Ga., which decorates helmets at youth baseball and softball events, was closed for six months last year. Owner Lisa Holmes applied for a grant on Feb. 7, the week the program opened.

The SBA is supposed to deliver the money within 21 days, but Ms. Holmes didn’t receive her grant until May, roughly three months after she applied. “Seems like they’re moving along, just very slowly,” said Ms. Holmes. Trying to get answers about the status of her application was a full-time job, she said.

Ms. Guzman said SBA was working to meet the 21-day goal.

False claim

Beyond problems getting aid money into the hands of those who need it is the problem of keeping it from thieves. In its October report, the SBA’s inspector general said the agency had “lowered the guardrails” to get aid out quickly. The SBA has disputed this characterization.

By February, the SBA had approved roughly $79 billion in potentially fraudulent disaster loans and advances, including multiple loans and advances made to applicants using the same IP addresses, email addresses, bank accounts or physical address, the inspector general’s office told Congress.

The SBA said it has since added safeguards. More than 160 SBA employees are working to address fraud, Ms. Guzman said, adding that Congress initially barred the agency from accessing tax documents, an important fraud prevention tool.

Last year, the SBA notified Neal Siegal, a commercial real-estate broker and property manager in Glen Cove, N.Y., that payments on his $9,400 SBA disaster loan were deferred with interest accruing, and the first payment was due on August 5, 2021. He had never taken out such a loan.

After filing a Freedom of Information request, Mr. Siegal received a loan document with his name listing a false phone number and email address. He contacted the SBA, the police, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Federal Trade Commission.

In late May, shortly after an inquiry from The Wall Street Journal about his situation, the SBA sent Mr. Siegal a letter that promised the government wouldn’t try to collect from him.

“Damage has been done,” Mr. Siegal said in an email, “including the great many hours (possibly hundreds) it cost me and the expense of trying to re-secure my identity.”

Tech trouble

As of January 31, the SBA has agreed to pay more than $890 million during the pandemic to outside contractors to assist the Office of Disaster Assistance with loan processing, customer service and other functions, according to a June GAO report. The disaster office increased its staff to about 10,000 full-time, temporary, and contract workers, the SBA said, up from roughly 1,000.

Loan processors were expected to review a dozen applications an hour, a task made more difficult because of shifting requirements and guidelines, said a former SBA official who helped process loans. The SBA said loan processors are now expected to review 22 applications a day and that the processing department provides written guidance to loan officers.

Technology snafus marred the launch of the Shuttered Venue Operators Grant initiative, designed to provide $16 billion to stricken theaters and other live venues. When the program opened in April, business owners struggled to register, received error messages and couldn’t upload required documents. SBA temporarily closed the application portal within hours.

A senior SBA official said the agency and Salesforce, its technology partner, had tested the portal for two weeks before the failed launch. At the time, a Salesforce spokeswoman said it worked with the SBA to resolve the initial technical issues, and that it was continuing to work with the agency.

One problem was the file upload function didn’t work because certain technology licenses hadn’t been registered, an oversight the SBA official called “a forgotten detail.” The SBA on Thursday said Salesforce had been responsible for registering the licenses. Salesforce didn’t immediately provide comment.

Elliott Cunningham, managing director of New London Barn Playhouse, said he spent about 50 hours preparing his grant application, gathering documents and studying a 57-page user guide. Income at the New Hampshire theater company had fallen 90% last year, he said. The technical glitches prevented Mr. Cunningham from submitting his application the day the program launched.

He successfully completed an application when the program reopened in late April but still hasn’t heard whether it has been approved. The theater is slated to reopen this summer, he said, and “Right now, I’m spending that money, even though I don’t know if it’s coming.”